Aligning Processes, Roles, and Metrics [in 9 Questions]

So you want to define a new process–or improve on an existing one. All you need to do is create a nice, streamlined workflow, right? Well yes, you do, but you also need to align roles and metrics. Here’s how, in 9 questions.

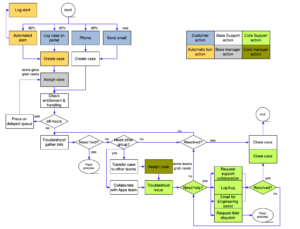

The process you define or refine must call out the steps to be completed, the order of completion, with decisions or branching along the way. Watch out for these three items.

- Are the steps defined at the right level of detail? I find that many processes go into too much detail, obscuring the overall flow. Instead, capture the details into work instructions. For instance, if you are working on a case resolution process, a step to “enter a case summary” is likely too low-level; a step to “create a case” is probably just right.

- Are you separating process from tooling? Focus the process on the “what” rather than the “how”. For instance, if a case is escalated to Engineering for technical assistance, note the escalation but call out the fact that the case status needs to be changed to “Pending Engineering” in the work instructions.

- Are unlikely exceptions burdening the flow? You want to consider common exceptions, but don’t worry about rare situations. For instance, call out that improperly-queued incoming cases need requeuing, but don’t worry about specifying what to do if a requeue is needed after a long period of troubleshooting. You have managers, they will figure it out.

But creating a strong process is only a start. You also need to consider roles.

- Who is capable of accomplishing each step? Generally speaking, we want to allow the largest possible pool of people to accomplish most steps in the process, as long as they have the necessary skills, of course. Don’t restrict actions unnecessarily. Use swim lanes or equivalent visual signals of who accomplishes what steps: that will highlight opportunities to keep ownership changes to a minimum.

- Who is allowed to complete the step? Some steps require a regulated or managerial authority. Fine, but always question the wisdom of restricting permissions. Do you really need manager approval for each RMA? Surely your senior reps are more than capable to do it themselves. Minimize special-power steps.

- Who is available to do the step? This is a big issue when individuals have multiple duties. If a particular step is time critical or a bottleneck, you may need to create a special role to ensure it gets done. For instance, you may need a subject-matter expert role to make sure that requests for help are responded to quickly.

A proper process definition also anticipates the metrics needed to monitor that it’s working properly. Think about three types of metrics.

- Has the process (or subprocess) completed? To measure completion, you will need an entry state and an exit state. Continuing with the case resolution example, it’s usually pretty straightforward to measure case opened to case-closed (but what if the case is reopened?)–but much harder to measure case-opened to case-diagnosed, for instance. Define entry and exist states.

- How long did it take? If you have solid entry and exit states, you can measure speed, maybe. But how do you account for customer actions? For off-hours clock time? (and does it matter?) Think of time measurements as you design the process.

- Was it done well? That’s the crux, right? Who cares if you raced through a process only to do it badly. Think of ways you can, ideally, capture quality through execution of the process itself. If not, define how to measure quality in other ways, usually via some kind of inspection, audit, or survey.

What have you learned by creating your own workflows? Please share your experience in the comments.

(Process definition is the core of the FT Works expertise. Ask me how we can help you define processes that align roles and metrics.)